|

NEWSLETTER #68 - SEPTEMBER 2009

Members will have noticed that the US pages sometimes carry an earlier date than the main newsletter. This is because the US page is added to the main paper newsletter when it is circulated in the US in arrear of the UK edition, so it is actually published between UK paper editions.

Page 1 | Page 2

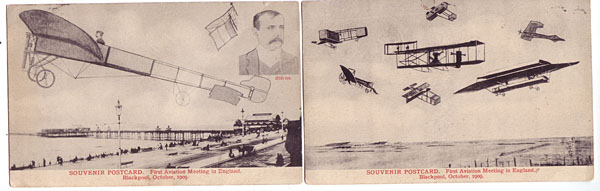

BLACKPOOL & DONCASTER OCTOBER 1909

From 15-23 October 1909, the first two flying meetings to be held in the UK were held. At this time flying meetings were supposedly regulated by both an international body, the FAI and a national body, the (later Royal) Aero Club. You could vaguely compare the situation with that which currently prevails for Formula 1 racing. What happened in 1909 was akin to a rival organisation organising a Grand prix on the same day as the official F1 event.

The Blackpool event was organised by Blackpool Corporation and the Lancashire Aero Club and followed the official rules. The Doncaster event was organised by Doncaster Town Council at Doncaster race course and promoted as “The First Aviation Meeting in England”. Clearly in 1909 local government in the North of England was confident and forward looking. What is less clear is whether the clash of dates was cock-up due to unawareness of the competing plans, or conspiracy to “spoil” the rival event. If the latter, the fact that one was in Lancashire and the other in Yorkshire may be significant.

Despite its unofficial status Doncaster featured Cody, Farman, Delagrange, and many other French fliers, but Blackpool had Bleriot, Latham, Voisin, A V Roe, among its aeronautical “celebs” of the day. Over 200,000 people were estimated to have attended the meetings at Squires Gate, which is still the airport for Blackpool, including some who came on special excursion trains from London. Postcards would have been prominent at Blackpool as a seaside resort and many were hastily and crudely adapted for the Meeting. In addition to the Voisin on the cover, here are two more by publisher Lenz & Weiss showing Bleriot and a collection of aerial devices, among which a Wright, Bleriot, Antionette & Voisin can be identified. Not sure about the device on the right.

By Phil Munson

It is right that Alcock and Brown get credit for making the first direct flight from the United States to Great Britain in June 1919.but what seems to be forgotten is that only about three weeks later the British Airship R34 also flew the Atlantic.

However, unlike the American NC-4 and Alcock and Brown, the R34 flew the more difficult East to West direction against the prevailing winds. What is more, they flew back as well.

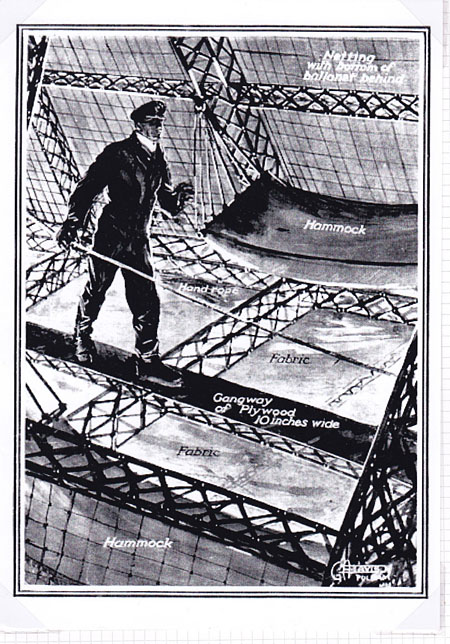

So, what was the R34 airship like. For a start, it is hard for me to imagine the size of the R34. A length of 600 feet and a diameter of 80 feet may not sound a lot. But imagine an airship as long as two A380 Airbuses and three times the diameter, trundling along, then you get some idea.

Bert Evendon “Sgt Engineer. Starb Watch Aft Car” recalled that the R34, a replica of the L-33 Zeppelin which bombed Britain in the First World War, was rather underpowered. Even though the maximum speed was about 65 MPH, at times they could only manage 35 MPH as it was difficult to keep all five engines working at the same time. It must take a long time to get across the Atlantic at 35 MPH.

Bert celebrated the sixtieth anniversary of the flight by crossing the Atlantic in Concorde. At the time, Bert, age eighty six was one of only three survivors from the flight. He has signed this card – probably a Science Museum issue of their model.

He recalls that the crew and VIPs slept in hammocks slung between five thousand gallon fuel tanks and highly inflammable hydrogen gas bags. They had only a catwalk ten inches wide to walk on. Underneath, the only thing between them and the Atlantic was canvas which would not support their weight. This view is in the style of the Illusrated London News reports

One thing which upset the crew before take-off is that, to save weight, they had to leave their mascot, the captain’s dog behind. So they were not pleased to find another member of the crew who was left behind for the same reason had stowed away. After threatening to “dump him overboard without a parachute” they let him work his passage. At the end of their hundred and eight hour flight they were nearly out of fuel and water. They had to drain the last drop of fuel from tanks they thought empty into buckets and cooking pots. One problem on arrival was that the Americans had no idea how to land such a large airship. Squadron Leader Pritchard parachuted down to supervise the landing. He thus became the first visitor to America to arrive by air. The return journey, with the wind, was much quicker in spite of even more engine trouble. The crew were very disappointed that instead of landing at their home base, East Fortune in Scotland they were diverted to Pulham in Norfolk. It may have been coincidence that, as they flew over the welcoming parade of hundreds of dignitaries and a band, the airship dropped its remaining water ballast soaking them all. Maybe coincidence or maybe spite, who knows. The R34 was lost in a storm on 27th January 1921. No crew were lost but several were killed in the R101 disaster a few years later.

Flying over the UK one cannot help but be struck by the number of dis-used airfields, either with existing runways or with the runway pattern only visible from above, like medieval field-patterns or iron-age settlements. The majority of these date from WW2 and had relatively short active lives. However , many others, often built near to city centres by ambitious councils had a brief active airline, club or manufacturer history before giving way to the pressure of land values. Some of these were the subject of postcards. Inevitably the home counties had several and those of Middlesex were featured in March 2000

Also in this category is Gravesend, Kent, the subject of What Do You Know in the last issue and updated in this. Another view, not showing much airport but a lot of DH.88 Comet is here. It is now under housing.

Staying south of the Thames, the impressive 30s style terminal at Ramsgate (NOT Manston) is shown on a retro card from the RIBA Architecture Library, (- with Short Scion).

By the 1950s the foliage had grown and Skyflights published this of their PA-22 G-AREV. Not much later it also vanished under housing and an indusrial estate.

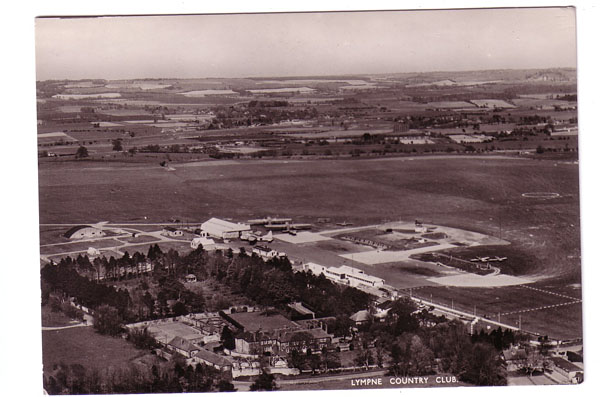

Further south but stil in Kent, Lympne was the original base for Silver City car ferries and remained as such until that airline opened Lydd (Ferryfield – now Ashford). Previously, it had been a “Country Club” field where flying was just one of the sports on offer. This persisted into the Silver City era and this airview with Bristol Freighters – by Skyfotos was issued by the Club. It is now – you guessed – under houses and industry though some buildings survive.

Lympne was also used by Skyways Coach-Air for their DC-3, bus-air-bus London Paris service. This card is by Norman of hastings, producer of many Ferryfield cards.

Moving west – here is a candidate for “most boring and uninformative postcard”. Portsmouth was home of PSIOW Aviation and manufacturer Airspeed but neither are shown here. Closed 1973 – more houses and industry.

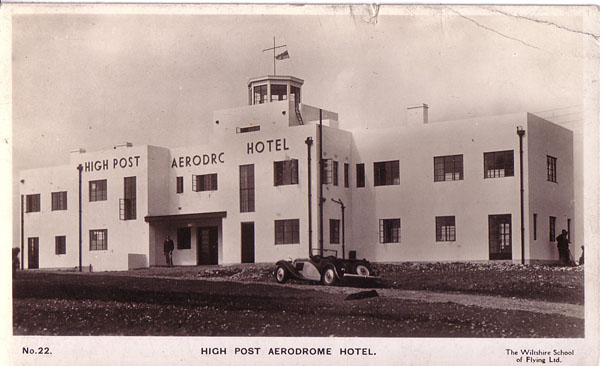

Below More 1930s architecture is on this Wiltshire School of Flying card of High Post Aerodrome, their then base near. Taken over for final assembly of Spitfires and then reverted to agriculture. The Flying School relocated to Thruxton.

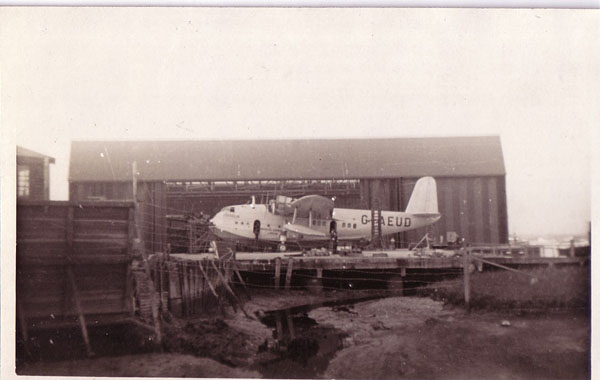

Next, two sites of a totally vanished way of flying – the Flying Boat. Empire boat G-AEUD Cordelia at Hythe on Southampton Water. She would be broken up there in 1947 but this is in Imperial days. The site is little changed but now in marine use.

Post WW2 a new marine airport was built in Southampton as part of the dock complex. Here is a BOAC Sunderland (Hythe) using the facility. The remains of the mooring docks seen to its left are still visible from the latest version of the pictured Hythe Ferry . Tuck SHN15.

The next card is of a little known field at Weymouth. It is not listed on the website http://www.homepages.mcb.net/bones/06airfields/UK/ukmenu.htm which contains much research on lost airfields. Treat this image from Mike Charlton, like several others for this article as if it was in What Do You Know.

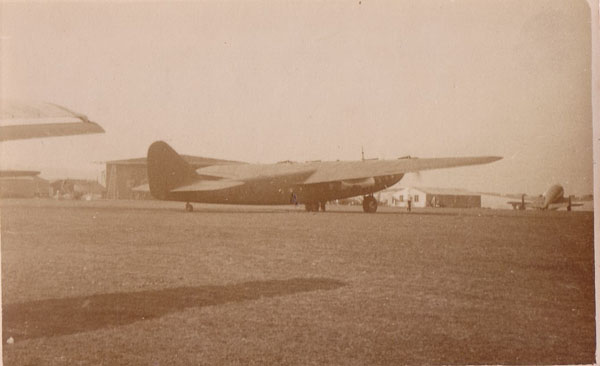

.... as could also be this next one which is untitled. Featuring a camouflaged Imperial/BOAC Ensign (G-ADSX?) & DH Albatross, it is most likely Bristol – Whitchurch to which much of Imperial Fleet was dispersed in 1939. If it is G-ADSX it must be pre June 1940 when this was abandoned at Le Bourget and subsequently taken into Luftwaffe service. Closed in 1957 and mostly re-used for industry.

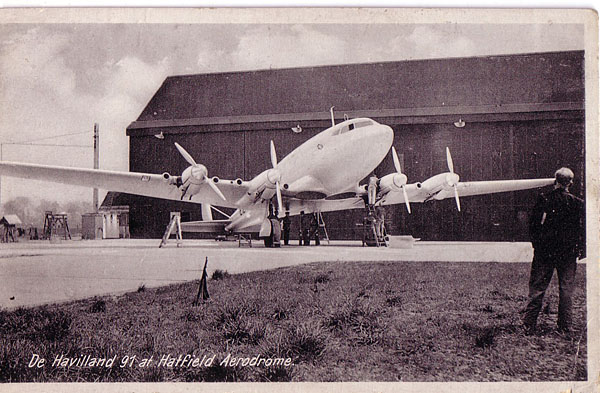

A prototype Albatross also features on the following card of Hatfield, Herts home of the deHavilland Factory. This is the only titled card known but the airfield features on some Comet cards both as background and ground landscape on air views. It closed relatively recently, in the 1990s. Some listed buildings remain and, in addition to the inevitable housing and industry, part of site has been taken over for archetypal 90’s reuse – a leisure centre and a “university”.

East Anglia probably has more old airfields proportionately than any other part of the UK, the majority being ex-USAAF. It has also had significant civil fields at Romford Essex, pre war home of low-cost precursor Hillmans Airways , and Ipswich Suffolk, home of East Anglian Flying Services, later moving to Southend and becoming Channel AW. No cards of either have yet appeared though. Returning to the London area there remains Croydon – a subject in its own right. The original Plough Lane terminal was one of the first to be “lost” being levelled in 1924. But like the Fairey Great West Aerodrome at Heathrow this was to be replaced by a greater, more modern airport – not to disappear under housing. This was it when still active – before replacement by the new terminal on Purley Way.

To be concluded – moving North and offshore

The last issue dealt with British India and Post partition India. This now covers the State of Pakistan and its Airline. This first card of Karachi Airport is undated and unstamped, so may be very early Pakistan or late British India. KLM Connie PH-TDB Batavia was delivered 1947 and had that name until 1949 so it could be either.

The first Pakistan airline was Orient Airways – Neville Stack ( see No 63 June 2008) was its MD prior to his suicide (see). Another carrier Pakair operated with DC-3s leased from Transocean in the US. This “far-from-home” unidentified AP- registered DC-4 at Santa Maria, Azores may be one of these.

Pakistan International Airlines (PIA) was formed in 1951 to take over Orient and operate international services with L1049C Constellations. One is shown at Heathrow on Skilton La10, possibly on delivery, as it is on the central apron when long haul still used North.

PIA, until recently have issued cards of their fleet but none are known after the Airbus A310. Here are four of a black and white set including L1049 in later colours, DC-3 (with background of the skeleton airship hangar at Karachi) Viscount and F27

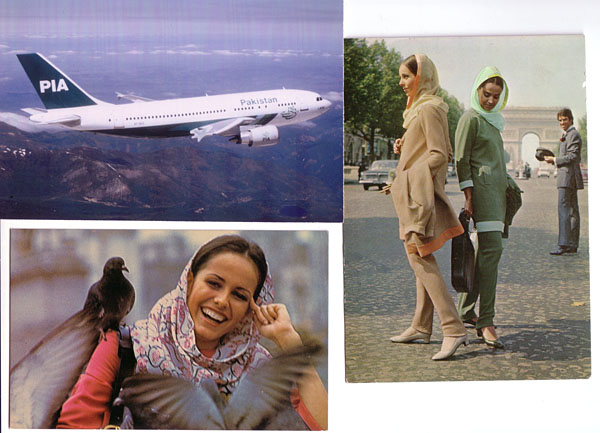

Subsequently PIA have featured 707, 720, DC-10, F27 & A310 on airline issues, together with some stewardess cards. The following shows some of the less familiar. The 747 is plain back and the F27 has a pre-printed message in Urdu. The A310 is the last known airline issue. The vertical stewardess card features “winter and summer uniforms designed by Pierre Cardin”.

|